Nothing to see here, just kneeling in front of the electric outlet appreciating Edison’s miracle!

– Homer Simpson

Remember the remodel? With the homeowner electrical permit? Well, the updated electrical code requires arc-fault protection, which is different from the more familiar ground-fault protection. Ground-fault interrupters deal with electricity that runs to an unintended ground, like someone standing in a puddle wielding a hair dryer.

Usually, arc faults are less immediately freaky. They occur when current jumps between conductors. For instance, a wire nut might not be on tightly enough, so the current arcs between the wires a tiny distance. Arcs are hot (duh) and can start fires, but they don’t automatically trip a regular breaker. To comply with the electrical code, we needed to install an arc-fault circuit breaker on every new and modified circuit.

THOSE OF YOU WHO UNDERSTAND HOW TO WORK IN A BREAKER PANEL WITHOUT FRYING YOURSELF, READ ON.

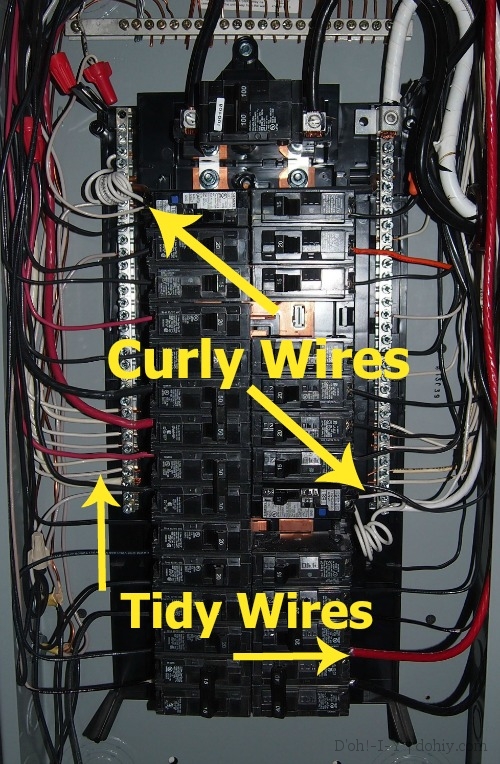

For a standard circuit, the hot/black wire from the line attaches to the breaker, while the neutral/white wire and the ground go to the neutral bus and ground bar respectively. (Stop reading if this is news to you!) The arc-fault interrupting breaker is connected to both the hot wire and the neutral wire. Then, a curly white wire extends from the breaker to the neutral bus. Dad taught me to keep panel wires neat, and the curliness is a little untidy, but that’s incidental.

Despite unsightly curliness, most of the circuits in question worked fine with the new breakers. But on the last modified circuit:

Installed. Turned on. Flipped. Reset. Flipped. Reset. Flipped. In denial, I bought a replacement breaker. Same result. So…there was an arc fault.

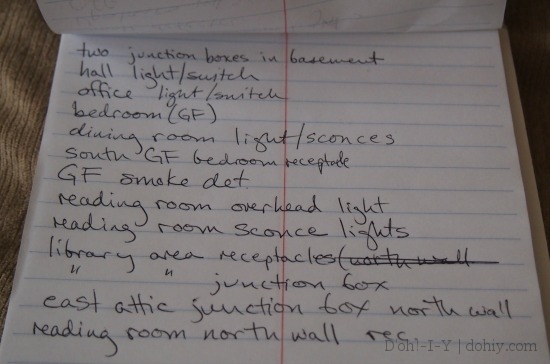

Finding and fixing the fault involves checking every connection on the circuit. Assuming there wasn’t a hole in the wiring somewhere (from a stray nail, for instance), there were 26 potential spots to check.

But it wasn’t that bad once we thought about it strategically.

- Divide and Conquer: If the circuit branches at a junction box, disconnect everything and then try each sub-branch separately. If one section doesn’t trip the breaker after you try everything under load, then that part’s ok. We eliminated about 80% of the connections this way.

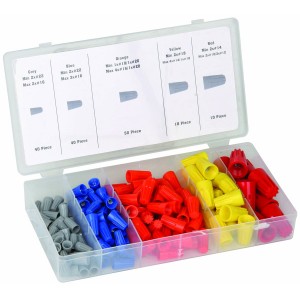

- Likely Suspects: If the fault is in the connections, then it’s probably in a wire nut rather than at a switch or receptacle. Switches and receptacles should have screwed-down connections, so prioritize checking junction boxes, light fixtures, and pigtails. Make sure that each connection is solid and that the wire nut is the right size.

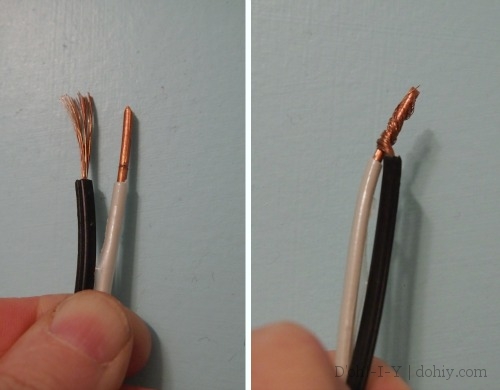

- Even More Likely Suspects: If you are still reading despite my many disclaimers, you know that many light fixtures have small-gauge stranded wires. They tend to go all frayed when connected with a single larger wire with a wire nut. To combat the problem, strip the fixture wire so it’s a little longer than the ends on the solid wire, then line the insulation up and spin the wires together with pliers before applying the wire nut.

This would have worked better with 14-gauge solid wire instead of 12-gauge. With 14-gauge, you can spin both wires for more of a barber-pole effect. Either way, make the stranded wire a bit longer to really wrap the solid wire for a good connection.

We found two problems. A junction box (pre-existing) had a loose wire nut, and a sconce light (installed by me) had a sub-par connection involving stranded wire. These worked fine with a regular breaker, which doesn’t sense these small faults.

The hunt was time-consuming, but doable (especially working together). If checking connections hadn’t worked, though, we would have called an electrician in a hot second (pun!). We don’t have the equipment or knowledge (or, in my case, the fortitude) to isolate an arc fault inside the wall.

Next: closing out the electrical permit!