Licking an electrical outlet will not turn you into a Mighty Morphing Power Ranger.

– Rock Bottom

I am not a morning person, so I don’t mind east-to-west jetlag. It gives me a chance to see how the other half lives. It’s amazing how much you can accomplish in a day when you’re out of bed at 4:00 am.

It’s one thing for jetlag to gently rouse you — it’s quite another thing for a Scary House Noise (SHN) to send you hurtling out of bed. Over the weekend, jetlag was just starting to wake me when I heard:

After hearing a second THWACK, I judiciously deployed our standard SHN operating procedure, which looks something like this:

After several more THWACKS, I located the noise in the main bathroom, coming from behind the outlet. The ground fault circuit interrupter (GFCI) receptacle had not tripped — GFCIs are designed to turn themselves off if there’s a problem — so using the handle end of my wooden hairbrush as an insulator, I pushed the “test” button. The outlet seemed to shut off as intended, but then: THWACK. Using the hairbrush, I reset it and waited. THWACK!

The GFCI outlet (sometimes called a “GFI”) in question, with cat. The testing and resetting buttons are in the middle of the unit between the sockets.

The THWACK sound was from an electrical short somewhere in the socket or in the wiring just behind it. A short is where electricity discharges along the shortest available route. Wiring is supposed to give electricity just one place to go to make it safer to use. A wiring short is like a tiny lightning strike. Inside your house, where you keep all your flammable stuff. That can’t be good.

Since the short was happening regardless of whether the GFI was tripped or not, I turned off the dedicated circuit for that outlet. I tested the outlet for power just in case, then I unscrewed the wall plate and the outlet and gently pulled everything out to take a look.

The wire insulation was all intact, and I didn’t see any nicks or scuffs through which the power could short. I stuck my schnoz down there and took a whiff; no acrid smell. The inside of the box showed no burn marks and nothing was heat-deformed. The body of the outlet itself looked intact.

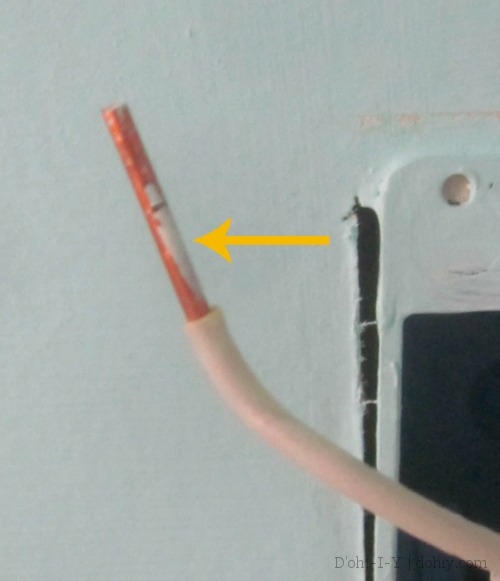

I loosened the connections and pulled out the hot and neutral. Both ends showed some scaling like white paint on the ends. These marks turned out to be the only possible evidence of the problem. Well, that and the THWACK had stopped, so I knew I was in the right place.

Some research indicated that a lack of evidence is not that unusual. While it was possible that simply tightening the connections would fix the problem, I could not be sure that was the actual issue (and the connections seemed plenty tight). A new GFI outlet is only about $10, so why risk reusing a bad unit?

In a bathroom (in the US), unless you have old wiring that has been grandfathered in, you need a 20-amp circuit that is dedicated to 20-amp bathroom sockets, which should be served by 12-gauge wire. IF YOU DON’T KNOW THE DIFFERENCE, call an electrician. Other reasons to call an electrician:

- You don’t know if your house is wired with copper or aluminum (the latter was common in the 1960s and 70s when copper prices were high — I grew up in an aluminum-wired house). Aluminum wiring requires special treatment to avoid thermal and oxidation issues that might arise when aluminum meets copper.

- There are only two wires in the box, or the hot/neutral wires are not distinguishable, or you don’t know if the wiring is the right gauge for the circuit.

- You’re in a bathroom or kitchen but the existing outlets aren’t GFIs, or they are on a circuit with other stuff.

- The supply wires are too short (or learn how to pigtail wiring).

- The GFI has onward wiring that goes to anything other than another bathroom outlet.

- There’s physical damage inside the box, or the box is really tight (or missing).

- There’s anything that gives you pause whatsoever!

If you don’t have any of these or other issues, GFIs are simple to wire if you follow the directions that come with the new unit. Be sure to read all the information provided with your specific outlet, because brands vary. Never guess when you are doing this work — you can always call an electrician, even if you already started the project.

Most of these units have push-in connections where you strip the wire to a specified length, insert the clean end into the unit, then tighten up a screw to make the connection. Much easier than hooking a wire under a screw head!

Since this wiring was new when we redid this bathroom about five years ago, there was enough extra wire in the box to work with (almost too much — I’m always surprised by the length required at rough-in inspection). I clipped off the scaled ends and stripped some fresh wire to insert according to the instructions.

After making the connections according to instructions, I carefully folded the wires back into the box and then tightened the whole thing down, alternating between the top and bottom mounting screws. Notice that there’s some wiggle room in the mounting holes to allow adjustments to keep things straight and level.

Add the cover and turn on the circuit. Use the test buttons to check that the outlet is working correctly. Listen for THWACKS!

You should test GFIs monthly. But even so, while shorts are rare, they can still happen (mainly in the pre-dawn hours). Not every Scary House Noise is a malfunctioning GFI, but when you are running around the house semi-clad, don’t discount them entirely.

2 Responses to That Can’t Be Good